Like everyone else ever, I had never heard of Kurt Vonnegut until college. I took a contemporary American literature course my freshman year and a student chose to write on the book for his term paper. He linked the Tralfamadorians to Italians, arguing that the circus/zoo exhibit that the Tralfamadorians place Billy Pilgrim in is analogous to Vonnegut's captivity in Dresden. Since Italians were part of the Axis powers, the Tralfamadorians read as hostile. Pilgrim's detention is not purely for the sake of providing an interesting exhibit, it is a way to demonstrate the Tralfamadorians' superiority over an alien species--and thus it resonates with Mussolini's and Hitler's ethno-nationalistic argument for a manifesto of race and master race, respectively.

Best Science Fiction Books 101-200

the top 100, I've placed them in this list of the next hundred best sci-fi

Ernest Cline - Ready Player Two Review

Ready Player Two is fan-fic of '80s and '90s culture along with fan-fic of Ready Player One. The navel gazing aspect of Ready Player Two's fan-fictioning of its own universe hurts the book immeasurably. A too-big chunk of the book is spent recounting the quickly fading glory of Ready Player One (and we can surmise, the quickly fading book sales and royalty checks now that the movie fanfare has quieted). I suppose if Player Three ever gets a turn at the controls, the narrative will be so bogged down by empty nostalgia that nothing new will happen at all.

Back to the Future and Unreliable Technology

Cormac McCarthy - The Road

The post-apocalyptic landscape is bleak in Cormac McCarthy's The Road. Food is scarce, so many of the ashen faced survivors of a meteor strike that has devastated the world's ecosystems have turned to cannibalism.

The Road is about survival, identity, and care for others. The central relationship is between a father and his son. McCarthy didn't name his characters, so Man and Boy will have to suffice.

Father and Son

McCarthy's inspiration for the book was thinking about his role as father to his son. The role of raising a child, teaching them what they need to know to not only survive but to live well, carrying traditions forward, letting go of control so that the son can mature and take on responsibility. But, McCarthy placed the time-honored tradition of raising a son in a disturbed world where survival is a battle. Living is often dependent on killing.

Review of Attack Surfaces - Cory Doctorow

Cory Doctorow writes the books that need writing. In 2020, that's a book about police surveillance and the firms hired to bootstrap big scary surveillance tech on the backs of militarized police forces, forces that were scary long before they could track the movement and communications of citizens. But Doctorow doesn't just pull back the cover on scary tech and the firms that operationalize it. He counterbalances the acceleration of surveillance and control with democratic resistance. Doctorow's heroes stand up to power and keep standing up to power until that power stands down.

12 Monkeys - I Want the Future to be Unknown

I want this to be the present. I want to stay here this time, with you.

Little Brother - Cory Doctorow

I'd read Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom before Little Brother. So, I knew that Cory Doctorow does more than tell stories. He extrapolates on the intersection of society and technology to consider what the future will be like. In Down and Out, the future is kind of odd. The only currency that matters is social currency. In other words, reading the (chat)room is all important. Down and Out is a utopia, a eu (good) and u (nowhere) kind of topos (place). As long as people like you, Doctorow's future Magic Kingdom offers a kind of immortality. Death is forever averted by loading one's backups into fresh bodies. The desire to cheat death through technology has a history with Disney. Walt had his body cryogenically frozen in hopes that doctors and scientists in the future could revive him and extend his life. But in Doctorow's world of extended life, life only matters if others value you.

An Interview with Robert G. Penner, Author of Strange Labour

Robert Penner was editor at Big Echo, which ran for four years and published boundary breaking SF. Now he's moved into his own boundary breaking with a bold, new book, Strange Labour.

Some books have a painterly quality. The images jump off the page, vivid windows into worlds that veer into territory at once strange and familiar. That's where Penner's Strange Labour begins and ends. Penner is an imagist in the quality of the moderns as much as he is a postmodernist and a genre writer. Strange Labour is literary SF, merging philosophy with PK Dickian skepticism, like anxieties about using marijuana for fear of scrambling one's own genetic material.

Cat's Crade - Kurt Vonnegut

This book "is devoted to pain, in particular to tortures inflicted by men on men." - from the Sixth Book of Bokonon

Paul Virilio's Original Accident considers how new technology creates ever greater possible calamities. The passenger airplane creates the air crash. The highway creates high speed car wrecks worthy of J G Ballard. Essentially, Virilio riffs on the balance between life and death, creation and decay. Everything is wolved by the fangs of entropy. But some technology resists classification here. Think of DARPA's soundwave based weapons, microwave based weapons, nuclear weaponry. None of that technology exists in some kind of mystic yin-yang between swell-ish and hellish. No, this crap was created to hurt people, to flatten cities, to maintain political sovereignty and economic might.

Annexing Invasion: An Interview with Rich Lawson

A singularly powerful aspect of Annex is that the aliens, though murderous, endow humans with powerful bio/psychic internal power qua weaponry. The weaponization of encountering the other is provocative. Rich's characters draw from power in their gut, the very place that we often use to describe our dislike of people and things: for example, "I had a gut feeling" or "I knew in my gut." With this gut power, Rich's characters can temporarily alter reality, creating holes in solid structures. The metaphoric work describes the disruptions in societies as a result of racism. Hate for the other sees through culture, art, and tradition, it masks reality with a fantasy of hate, a fantasy that insists that a people group are worth nothing, are nothing.

Lawson has published dozens of short stories, beginning in 2011. He was born in Niger and now lives in Ottawa, Canada.

From Space Opera to Cyberpunk: Influences of 13 Science Fiction Writers

Rapid Transmission asked several science fiction writers to talk about what had the greatest impact on their writing and how such works, whether books, movies, or games, reflect on their own work.

Man Plus - Frederick Pohl

Frederick Pohl's Man Plus is a cynical consideration of posthumanism. Rather than terraforming Mars, scientists operate on a spaceman to create a being suited for life on an otherwise inhospitable planet. Why is this cynical?

It's All a Mating Dance: An Interview with Mark Everglade

Science Fiction encapsulates far more than hard science applied to storytelling. The genre considers history and futurity, gender and sexuality, war and the dynamics of civilizations, the human mind and body, technological progress and regress, life and death. Science fiction is at once about possibility and the hard limitations that humans face, whether of their own strength and lifespan or of the secrets of the near infinite expanse of our universe. And the inner space of the mind and body, grey matter and genetics, are just as fascinating as the vast reaches of outer space.

Empire Records Analysis: Or, Anarcho-Syndicalism Rocks!

I first watched Empire Records in 2000. I was in college and a movie about young, edgy people working together in an independent music store sounded fun. At first blush, the movie comes off as a bunch of posturing young people that aren't comfortable in their own skin. That element is there, to be sure, but to treat the movie as "Just Another Teenage Movie" would be to miss out on a powerful under-riding narrative of collectivism and anarcho-syndicalism.

Beggars in Spain - Nancy Kress - Probably a Communist Text

What draws me to Nancy Kress is her background studying English, getting a degree from SUNY Plattsburgh. I'm no New Yorker but an English program is an English program. Add to that that I came up with the novum for this novel while brainstorming ideas for short stories.

I told my friend Bob Wilson, "Hey, what do you think about a story with people that are biogenetically engineered to not require sleep."

"Yeah, that's a good idea, but it's already been done. Go read Nancy Kress's Beggars in Spain."

I did read it. I liked it a lot. I also never wrote a story about the sleepless. I guess I still could. After all, part of science fiction is that it operates as a megatext where everyone recycles the same ideas over and over, hopefully adding to them and thinking about concepts in more complex ways--but not always.

That leads in to questions about entertainment vs. value. Science fiction is sometimes a galvanizing force for the future or a predictor of ugly things to come--ugly things best avoided, but more often than not science fiction is just about entertainment.

High-Tech Corrupted Worlds: A Discussion with Elias J. Hurst

Watching Do the Right Thing in 2020

"At the end of the film, I leave it up to the audience to decide who did the right thing." - Spike Lee

If you watch Spike Lee's Do the Right Thing, you won't feel like you're watching a movie made three decades ago. Well, maybe you will, but I didn't. I know that I have a nostalgia for all things '80s and '90s and can run on the media from that era forever, constantly amazed at the creativity and beauty that came out of that time. And with music featured prominently by Public Enemy and others in the film, I get all that I want and more out of it. But this movie does more than merely resonate with my admittedly deep nostalgia.

Do the Right Thing tells a story of American racism that hasn't changed all that much over my lifetime. It hurts to see that. I first saw a clip of Do the Right Thing in 2012 as part of Amit Baishya's Theory course at Ball State University. Nearly a decade later, the movie continues to reflect a reality continuing to play itself out on the streets of our country with young black men choked to death and young black women shot and killed by the police.

How many Radio Raheems have disappeared? How many more will die before we collectively agree that enough lives have been lost? Malcolm X says, “The price of freedom is death,” but I hope that freedom for minorities and the disenfranchised in America arrives without filling our cemeteries with young black and brown bodies.

In the movie, the neighborhood drunk, himself an unlikely but lovable hero, tells Spike Lee's character Mookie to "Do the Right Thing." Mookie tries to follow that counsel. But in a neighborhood and country rent by racism, it's not always clear what the right thing is. As Robert Chrisman describes, "Do the Right Thing leaves one with a melange of contradictory and, at times, confused messages that suggest that the film has no clear vision of racial relations in a métropole (53). Chrisman points to a plurality of attitudes and perspectives in the movie. Doing the right thing isn't clear when messages abound. Should one fight the power, as a song by Public Enemy admonishes, should we give in to hate for the other, or should we make every attempt to accept those around us, even if they are different?

Rhetorical question notwithstanding, differences abound in Do the Right Thing, ultimately leading to violence. During a flashpoint moment, Mookie picks up a garbage can and tosses it through Sal's Pizzeria, inciting the crowd to loot and burn the restaurant. But Mookie doesn't do anything further. He sits across the street in dazed disbelief at the destruction playing out before him, as if he's not sure if he did the right thing or not. He had already been standing up for himself to Sal and Pino, Sal's racist son. But upon witnessing Radio Raheem's death, he's goes beyond words directly to action. Mook is working out the tension between Martin Luther King Jr.'s call for nonviolent protest and Malcolm X's promotion of violence as a catalyst for change.

In the aftermath, Mookie sees that the other right thing is to work to support his girlfriend Tina and their young son, Hector. To this end, he doesn't accept a handout from Sal, but only what he rightfully earned. He doesn't have a ready solution to the difficulties he now faces without employment, in a neighborhood where hate has risen up to overcome love.

As a way forward, the movie offers a lot of suggestions. Maybe we all just need to chill. Or maybe salvation will arrive from an infusion of cash from an insurance claim, the ever present reminder of capitalism's victory, if not over racism at least over seeing the haves become the have nots. But King's and X's picture is tacked onto the wall at Sal's Pizzeria. So, a recognition of black heroes is gained. All through Do the Right Thing, Lee gives us black heroes. The great accomplishments of black musicians are front and center and midway through the film, we even get a long list of many excellent artists, from Sade to Dr. Dre to Miles Davis.

Probably the most important statement of the movie is that a clearly victorious way forward isn't postulated. Rather, 1989 carried its own nostalgia for the power of the Civil Rights movement and the great cultural achievements of a century's worth of black artists. But, at the same time, that nostalgia is contrasted with a darker picture of black bodies sprayed violently by firehoses and policemen attacking black men in a clear continuum with a deeply racist past.

We've got to break out of that continuum. We've got to do the right thing.

Sources

Chrisman, Robert. “What Is the Right Thing? Notes on the Deconstruction of Black Ideology.” The Black Scholar, 21.2, 1990, pp. 53–57. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41067684. Accessed 28 June 2020.

1000 Year Old Science Fiction Writers

Question 1: What is the creative capacity of the human. Would time allow a human to keep digging, keep finding more stories to tell? Or does imagination run out at some point? I suspect that creativity could continue, but one's perspective would surely alter. The human perspective is already quite different in the various stages of a 75-80 year lifespan. Everything a person writes until they reach twenty years is mostly garbage. Then you get a flowering born of a maturity of vision and skill chained to the rocketing excitement and newness of youth. This doesn't last, of course. The following decades gradually give way to greater perspective and, commonly, a decrease in passion or vital energy.

But what would happen if this greater perspective just kept on going for a thousand years? I suppose that few people under the age of 200 would find a great deal of interest in the writings of, say, a 700 year old. Not least because it would take a long time to build up the requisite knowledge needed to appreciate the work of a septuacentennarian.

Question 2: Provided a writer could build up an income stream from previous works over the course of a few centuries, would they care to continue writing? Highly successful artists with our current lifespans commonly pause to rest from creative endeavors for a year to a decade of time. Consider Steely Dan, who went on a hiatus through the '80s. Or consider Thomas Pynchon, who didn't publish a book after Gravity's Rainbow (1973) until almost two decades had passed with Vineland (1990). Though, Pynchon is an anomaly. He takes such care with every word and sentence in his books, that maybe it really just took that long for him to finish his project.

Okay, so what I'm saying here is, if I wrote two hundred novels over the course of three hundred years, earning enough to let the stock market do its thing for me, I think I'd be ready for a break.

Question 3: Would readers keep reading your stuff several hundred years in? For the argument, let's say that Stephen King had another 900 years to keep writing. Would you be down to read eighty more Dark Tower books? That's a lot of tooter fish sandwiches. My guess is that people would continue to be fans of their favorite authors across the centuries. Unless . . .

Question 4: If everyone is living for centuries, at what point do former fans turn their back on reading and take up the pen. With a thousand year life spans, surely almost anyone could learn to perfect the literary art.

Question 5: Do other forms of media and forms of entertainment along with advanced AI eclipse the need for human writers and human work? Maybe thousand year old men do little more than recline on a throne of forgetfulness as robotic servants buzz around them, clipping toenails, changing catheter bags, massaging striated muscles, fetching channel changers, writing original screenplays, the whole works.

Taking all these questions into account, I assume that if a science fiction writer could live to be 1000 years old, they would give up on writing long before their abilities flagged or their readership vanished.

Fortunately, I don't have any of these problems. So, cheers to everyone as I continue writing.

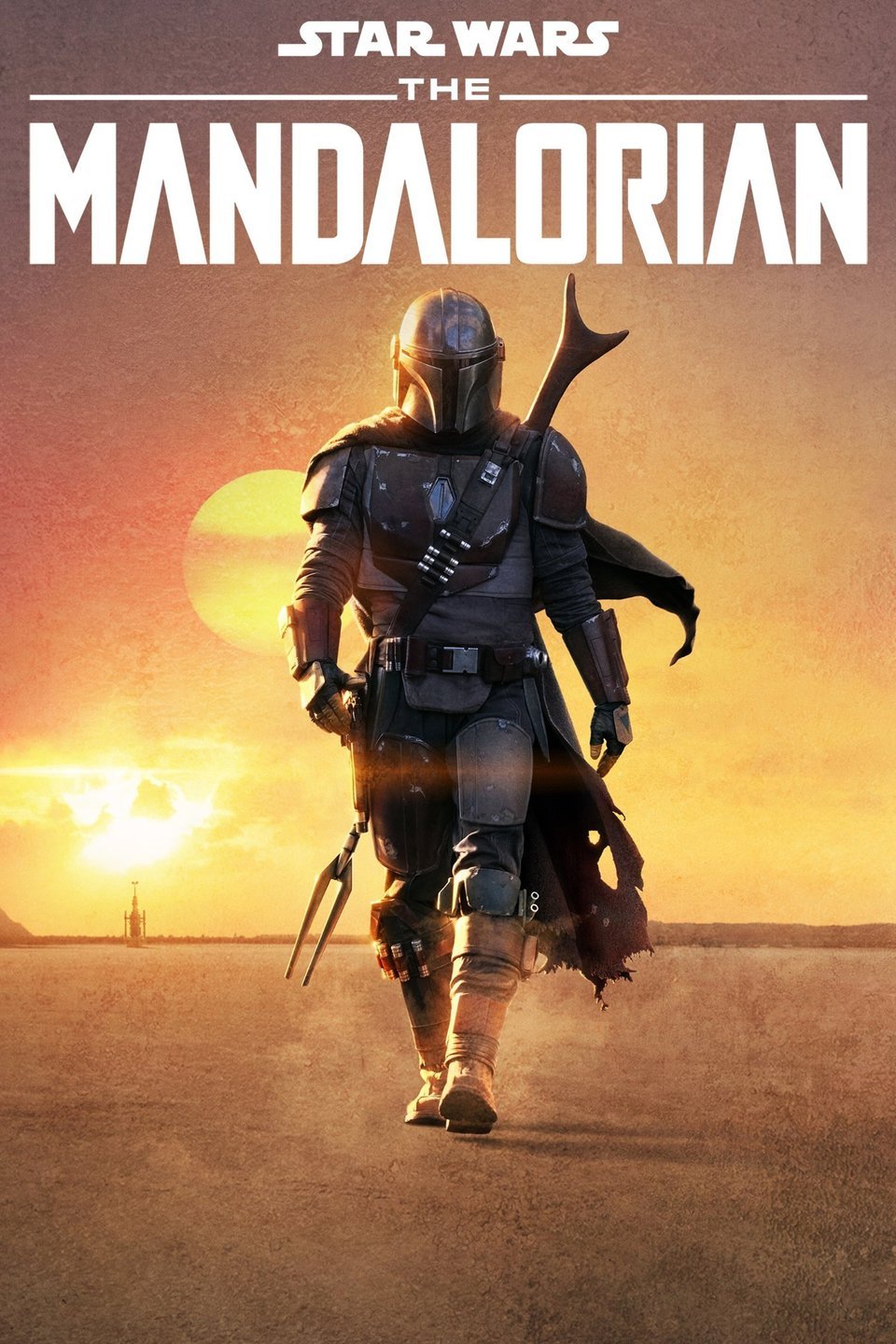

The Mandalorian

So, space opera is sometimes not much more than westerns in space. That's The Mandalorian for you. This isn't necessarily a criticism. While the series has a couple of heavy-handed "You're watching TV" moments, the western themes are mostly deployed intelligently and don't crowd character development. The exceptions? A gratuitous learn how to ride a horse-like creature sequence and an interminable standoff, with Imperial soldiers doing a lot of standing around on a street outside an Old West looking storefront and the Mandalorian's cohort doing a lot of hand wringing inside.

The State of Science Fiction

One of the great difficulties of pushing science fiction in 2020 is information fatigue. You can also call it future fatigue, a problem where the oddities and fears we all used to relegate to the future keep piling up in present reality.

In a society with a dearth of technological advances, science fiction is absolutely needed. Consider that the golden age of SF in the US came during the lead up and beginnings of the atomic age and the space age. But when science fiction is reality, what do you do then? You want to return to nature, breathe in some rarefied air, gain the perspective you can only get when you turn off all the devices for a weekend and spend time looking in the glowing embers of a fire. The last thing you probably want to do is pick up a good technothriller about a killer virus from Wuhan that causes already distressed relations between the US and Chinese superpowers to boil over.

Rimi Chatterjee: Love and Knowledge and Yellow Karma

The twenty-first century operates on the money-as-value system where one consumes or is consumed. People are nothing if they don’t contribute to the market. Global politics has turned into a complex calculus, with nationalism returning to pre WWII levels led by toxic, tiki-torch toting masculinity. The global village is sick and the globe is sicker, riddled with plastic trash, radioactive waste, and carbon with nowhere to go.

Robert Heinlein maintained that science fiction must put humans in the center of its stories. That axiom has held through the atomic age and has perhaps never been more important than now, a time, as Rimi Chatterjee describes, full of hanyos. Half man and half devil, the hanyo lives for himself and, more to the point, kills for himself, using up people and resources without regard for the future, for sustainable culture, for the inner life.

Rimi Chatterjee is an English professor and Indian SciFi writer, following in the tradition of Ursula K. Le Guin, C. J. Cherryh, and Joanna Russ. She has three published novels, Black Light, The City of Love, and Signal Red. Her novels fuse hard SF with twenty-first century social and economic perspectives. Her writing is rich with the promise of a technologically enhanced future and richer with a compassionate embrace of the human condition.

Dr. Robert Doty's Science Fiction Collection

Dr. Robert Doty was my friend and mentor. I first met him as a boy at Campbellsville University where my dad taught New Testament and Greek in the Christian Studies department. The picture above is from 1991-1992. Years later, I took Dr. Doty as an undergraduate and a Master's student, studying English Literature. While working on a PhD in English Literature, we met regularly to discuss critical approaches to texts.