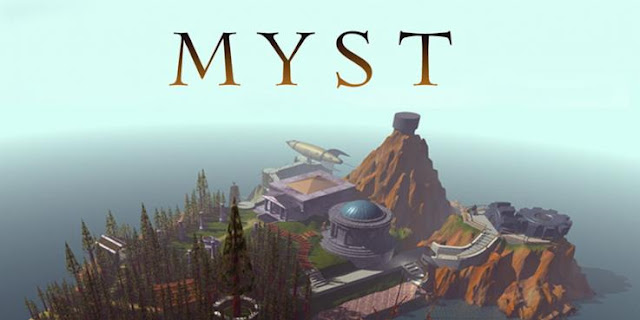

The Myst video game, released for the Macintosh platform in 1993, is a graphic adventure puzzle video game designed by brothers, Robyn and Rand Miller. It was developed by Cyan, Inc., published by Brøderbund. Let's just take in the Myst island for a glorious moment. Behold the beautiful pine forest! Marvel at the inexplicably big cairn-like gears atop lookout point! Consider the oddity of a spaceship on display at the island's northernmost point. Enjoy the throwback Greco-Roman architecture of the library and the planetarium.

Trial Versions of Vids

Yes. What's not to enjoy with this game? I was enamored with Myst when it first released. I actually played a trial version before getting the full game. I think the trial was limited to the library. You could check out the blue book and the red book, though without any blue or red pages all you get is the sound and color of television tuned to a dead channel, thanks William Gibson. Back in the times, video games magazines sometimes had trial CDs in them. So, you'd get to preview a bunch of games. I fell in love with the Heroes of Might and Magic series this way as well. But that's a different story.

Will Atrus Find Catherine?

Back to Myst. Myst was the best looking game I'd ever seen. Queue the dramatic Myst music and the husky basso voice of Atrus musing on and on forever about his Catherine.

Being raised on Nintendo games, which are, for the most part, all based on twitch gaming, it was nice to play a slow game, wandering around a virtual space to take in the sights and sounds, writing down clues, solving weird puzzles.

I Played Myst on a Junk Computer

Now, truth be told, it's been a long while since I've played Myst. I wonder if the load time for moving around the islands would now feel a bit too slow. I know if I was returned to the '90s, I'd probably crack at having to drag through the dial-up protocol every time I wanted to get on the internet. I know I'd grimace at waiting half a minute for an image to load on a website. I originally played Myst on a computer with 8 MB of RAM. For those of you that don't know what I'm talking about, 8 MB of RAM isn't enough to ram your way through anything, least of all a, then, cutting-edge video game. I had to restart the computer every hour or two, depending on how many cutscenes I'd been through, to keep the game running smoothly or to even keep it running at all. Now, this was no fault of the game, per se, but I'd be willing to bet that the lion's share of people playing the game back then encountered the same kinds of slowdowns.

Myst was Psychologically Unsettling

Why was Myst kind of frightening? It's not because the game was especially frightening in and of itself. As I've already mentioned, it's a slow game. You take your time to wander around solving puzzles. Now, at times, the music does take on an otherworldly, put-you-on-edge quality. But more than the music, the frightening aspect of the game comes as a result of its symbolic nature. The opening sequence puts you, the player, into the game. You've fallen through a rift in time, and now you are on a weird unpopulated island full of riddles and steampunk tech.

Myst and the Ubi Sunt

So, then, Myst drops you into the ubi sunt, the "where are they" story. What's an ubi sunt? It's a bit like Goldilocks and the Three Bears. A traveler wanders along, finding evidence that people once lived somewhere. But unlike the three bears story, a proper ubi sunt doesn't settle the question about where the former inhabitants of a place went to. No, they're gone for good. Okay, I know that we eventually find out where the people are that were once on the Myst island, but for most of the game we don't, which places us pretty squarely in the realm of the ubi sunt for hours of gameplay. And this is where the frightening aspect of the game comes in. Ubi sunts cause us to question not only what happened to bygone civilizations but make us consider that one day we will also disappear from time.

Abandonment, Isolation, Uncertainty, and Loss

Consider giving a thirteen-year-old a game that drops them into the headspace of abandonment, isolation, uncertainty, and loss. Like the puzzles you're trying to solve, the symbolic nature of the game is itself an, at first, unrecognized puzzle. I recognize that my own experience of adolescence isn't universal, but imagine for a moment playing a game that you gradually realize reflects your own existential crisis. So, here I am playing a game to escape from feelings of uncertainty and isolation and then those same feelings surface in the game like once sunken ships.

I imagine that the future of gaming will do a lot more of this sort of thing but much more deliberately, more tailored to the individual. AI will read the player, constructing a theory of mind for the player as a result of the in-game choices they make and as a result of analyzing speech patterns, user time, and by watching the gamer game. The game, continually reading the player, will structure a game that the gamer wants or maybe, just maybe, even needs, deep down in his gamer soul.

Myst was Made by Nerds for Nerds

But Myst was created by nerds just like me. They felt all the same feelings of isolation and uncertainty about life that I felt. So, in creating a game that reflected their human experience, they reflected mine. And, man, was it chilling! I remember going to sleep after Myst sessions with feelings of dread, feelings of the uncanny. And what does one do in the face of dread and the uncanny? They play more of the game. And then they play Riven and, like me, never figure out that the sounds are the way to solve the puzzle until they read through all the GameFAQs.

More Rapid Transmissions:

More Rapid Transmissions: